I've been trying to help a woman who inherited an old

grand piano. She has no place for it, and doesn't want to go through the trouble of selling it (it would not fetch much). She has found someone to give the piano to, but he's very nervous about maintenance costs.

They each consulted local

piano technicians. Her technician worked for a piano dealer, so he pronounced the piano a piece of junk, and suggested they get rid of it and buy one of his. All this did was make everyone paranoid about the piano's condition.

His technician was a full-time

rebuilder. He loved the piano, said it was wonderful, and suggested that $14,000 would be sufficient to bring it back to life. All this did was make everyone paranoid about the cost of piano maintenance.

Neither of these technicians said anything wrong. They were merely talking up their lines of business. Dealers sell, rebuilders rebuild. Ordinary piano owners, however, don't know about these distinctions among technicians.

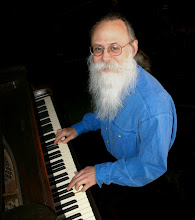

The woman contacted me through a mutual friend, and I tried to help her over the phone. Because my specialty is repair, I of course suggested repairing the piano. I gave her an idea of what it might cost, based on her description of what the other technicians had said, but I cautioned that without inspecting the piano, I couldn't be sure. The problem was that the piano was three hours away from me.

After a number of phone conversations, I thought what the hell, and arranged to go see the piano, giving the owner a break on the cost, friend to friend. I was also thinking, though, that if there was enough work and the means to pay for it, and if I could be put up for a few nights, it could work for me. I did this once for a family near New York City. They had a spare apartment, and room in the basement for a makeshift shop, and I spent a week reconditioning their old Steinway upright. They fed me dinner each night (with wine!)

The piano was exactly what I expected: about seventy years old, worn but not abused, no significant damage, playable. It had been an upper quality piano out of the factory. Someone had done a pretty good job of replacing the

hammerheads at some point, and the bass

strings and

tuning pins were replacements, too. The piano was even at

concert pitch! I could have just tuned it, and it would have been fine for casual use or beginner's lessons. I drew up a list of things worth doing, all those little maintenance things that had gotten overlooked over the years. It was a great candidate for rebuilding, if anyone had the money. Otherwise, it could be used for another decade, maybe two, but not for professional or heavy use. I would have been happy to do the work.

The intended recipient has been speaking with me, still nervous about long-term maintenance costs, whether the piano is "worth it," wondering if I would do the work piecemeal. I just wrote him a long email, and I thought I'd post some of it here.

The reason why you can find old pianos for free or cheap is because they all need work, and continue needing work. In fact, new pianos need maintenance too, but it gets put off until finally the piano is unplayable and needs a lot of work all at once. Things then just get worse as the maintenance is put off for decades.

An old piano is like an old car - you expect it to need repairs regularly. It just gets worn down. Things loosen or come unglued here and there, it starts making noises. Some of this is easily corrected (depending on who you talk to), the rest you just let go. The key is finding the person who will keep your piano going and not try to gouge money out of you. Like finding the car mechanic who will keep your old clunker going enough to get to the grocery store on a regular basis. The only time you run into trouble is with a piano tuner who doesn't want to do repairs, and who tries to sell you something else, like a new piano or a full rebuilding. Those things are fine if that's what you want. Otherwise, stick with the guy willing to do repairs and you'll be OK.

Here's my advice. Take the piano, it's a pretty OK piano. Find someone to come and tune it. If he (or she) says it can't be tuned, or it needs to be rebuilt, throw him out and find someone else. If he says there might be a little work needed with the tuning pins to hold the tension, then let him do a little work. Only a little. If he says your soundboard has cracks, say "Yes, I know," and leave it at that.

Then play it. It's already playable, just needs the tuning.

Later, say a year or two or three from now, you'll have a better sense of what you'd like from the instrument. Maybe some regulation, maybe some voicing, maybe the inevitable miscellaneous repairs. But keep up with the maintenance. It won't cost you much if you keep up with it.

Consider, after tuning, getting the soundboard fixed. Not all tuners know how to fix an old soundboard without going through all kinds of craziness, so you might have to hunt around, but that would have great benefit for the piano.

Clean and lemon-oil the case, use a scratch cover for the dings, I'm sure you could do this yourself over a weekend. Dust off the plate and strings, use a vacuum if needed, wipe the damper heads (in the direction of the strings). Ask the tuner to run a cloth over the soundboard, under the strings. We have little gizmos for doing that. A clean piano will make you feel better.

If you do want to hire me a year or so from now, the reconditioning offer is still open. I could take care of all those little things that need attention (like the soundboard, and tapping all the tuning pins in, and seating the strings on the bridge correctly, and correcting the voicing and the regulation, and leveling the keys and tidying up the keytops, cleaning up the dampers, etc.) Of course, if you find the guy up there willing to do all these things (and do them correctly), then you'll be all set.